As energy-intensive air conditioners are increasingly being installed to combat global heating, district cooling networks offer an alternative. But what are the pros and cons?

Representative image. Photo: Niall Kennedy/Flickr (CC BY-NC 2.0) District Heating

While designed to cool our homes and places of work, air conditioners powered by coal, oil or gas energy simultaneously increase emissions of greenhouse gases that heat the planet. Often installed on building facades, air-conditioning units also contribute to warming cities through the release of waste heat.

They also consume a lot of electricity on hot days, which can overload energy grids and contribute to the triggering of blackouts.

To address these problems, numerous major cities such as Paris, Munich, Hong Kong, Singapore, Dubai and Toronto are building large, efficient central cooling systems that consume less electricity.

There, they are used by hospitals, hotels, data centers and large buildings, and operate by pumping cold water through a network of pipes.

More efficient than household air-conditioning systems

In modern cooling technology as used in refrigerators, air conditioners and heat pumps, a gas is compressed in a closed system where it becomes a vapour. The process releases heat. The pressure is then reduced, causing the vapor to warm again and become gaseous. In the process, heat energy is extracted, creating a cooling effect.

Using various measures, large refrigeration plants can produce cold in a more environmentally friendly way than small plants.

Many municipal utilities, for example, use natural cold from rivers, groundwater, lakes or the sea. This also means such plants need far less energy.

“We try to use as much groundwater or city streams as possible as the main cooling supplier,” said Stefan Dworschak of Stadtwerke München, a city-owned communal company that supplies electricity to more than 95% of Munich’s households.

Like other district cooling networks, the one in the southern German city of Munich has ice storage facilities. Ice is produced there using large chillers, particularly at night, “when electricity consumption in the city is low, creating less pressure on the power grid,” Dworschak told DW.

The cold created at night is then released during the day to meet the needs for cooling in the buildings.

Cooling with heat: Absorption cooling

Cooling can, however, also be generated with heat. In the Austrian capital of Vienna, for example, waste heat from a trash incineration plant is used to power a so-called absorption chiller.

By intelligently combining different technologies, natural cooling sources and existing waste heat, central cooling systems often require less electricity. In Munich, the savings from centralised cooling compared to decentralised are “50 to 70%,” according to Dworschak.

Combination of cooling and heating technology saves energy

Like district heating networks, district cooling networks also have disadvantages. Investment costs are high, and pipes have to be laid underground in the city and connected to buildings. Both cooling and heating energy gets lost as it passes through long pipes in the ground.

These losses are particularly high if the water is either very hot or very cold when in transit. Experts highlight the savings potential here through the laying of combined cooling and heating networks — as is increasingly the case in Europe.

One such example is in the Moosach district of Munich. There, the municipal data center is connected to a district cooling network that uses cold to cool the servers and pumps heated water back into the return line from the cooling network.

A few hundred meters away, this heated water is used for the heat pump in an apartment block. It heats 114 apartments and then pumps the cooled water back into the cooling network.

“This is a good way to increase efficiency even further. We want to push ahead with the expansion of such networks for this reason as well,” Dworschak said.

These combined cooling and heating networks are particularly useful in temperate climate regions such as Germany where there is the potential for a dovetailing of the demand for cooling and heating. When waste heat from cooling systems is used for heat pumps, for example.

Building insulation drastically reduces cooling demand

The most important factor for efficient cooling, however, is building insulation, says Wolfgang Hasper of the Passive House Institute in Darmstadt. The independent research institute calculates the energy consumption of buildings, organizes conferences and trains architects worldwide in energy-efficient design.

If buildings have good facade and roof insulation, windows with double or triple glazing, good shading and intelligent ventilation, “then the heat from outside doesn’t get in,” Hasper said.

Well-insulated buildings need up to ten times less cooling energy than a building with a lot of glass, no shading and no insulation. Hasper says that if insulated apartments in warmer regions were efficiently equipped with decentralised air-conditioning systems, it would lead to significant electricity savings.

Insulation is a good alternative to district cooling networks, he adds, because property owners can install it themselves whenever they want, without having to wait for the expansion of a district cooling network where they live. What’s more, he adds, insulation and cooling technologies can often be used in conjunction with photovoltaics, especially in hot countries.

Ample sunshine “means solar plants can generate a lot of power when electricity demand for cooling purposes is high,” said Hasper. “It’s a good correlation of supply and demand. A good match.”

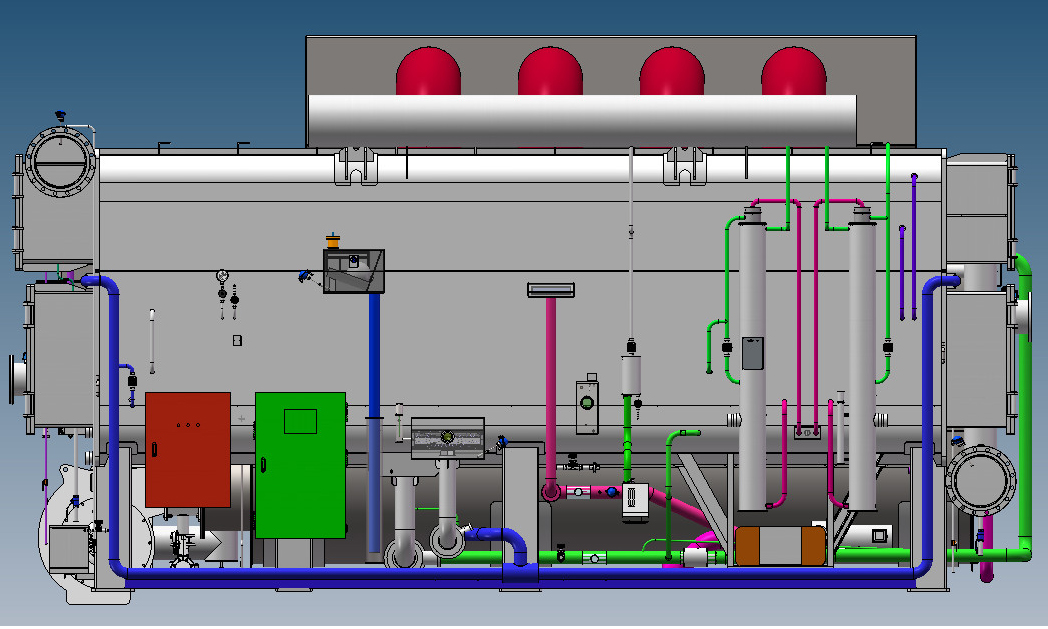

Dual-Effect Absorption Chiller This article was first published on DW.