Gun metal terms get bandied about in product literature and the firearms press as if everybody knew just what the hell they were talking about. If you're in the dark about what it all means, read on.

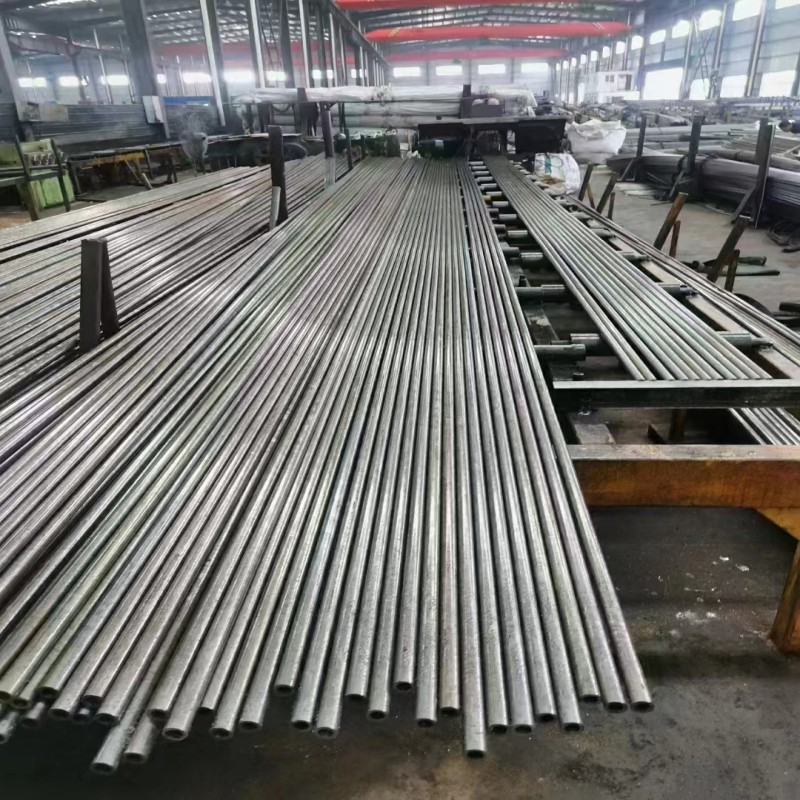

What is steel? And why is it so important in gun building? Simply put, steel is iron with enough carbon in it to allow hardening—but not too much because that makes the resulting alloy brittle. Steel does not have pores; it consists of crystals. (Brief rant: Had I any hair left, I'd be pulling it out every time I heard of yet another lubricant that "gets into the pores of the steel.") The shape, size and alignment of those crystals determine the mechanical properties of the steel in question. The crystals of steel are described by their sizes and shapes, and they have actual names such as austenite and martensite, cementite and ferrite. Stainless Steel Quarter Round

Steel can be alloyed with other metals such as nickel, chromium and tungsten—as well as non-metallic elements as molybdenum, sulfur and silicon. Those alloying agents add useful things to the mix, such as easy machineability, corrosion resistance, abrasion resistance or tensile strength without brittleness to the steel grade in question.

The Society of Automotive Engineers uses a simple designating system, the four numbers you see bandied about in gun articles. Numbers such as 1060, 4140 or 5150 all designate how much of what is in them.

The first number is what class—carbon, nickel, chromium and so forth. The next three numbers tell you how much of what is in them. Let's take as an example the steels in the classic barrel argument amongst AR owners: 4140 steel versus 4150 steel.

4140, also known as ordnance steel, was one of the early high-alloy steels, used in 1920s' aircraft frames and automotive axles in addition to rifle barrels. It has about 1 percent chromium, 0.25 percent molybdenum, 0.4 percent carbon, 1 percent manganese, around 0.2 percent silicon and no more than 0.035 percent phosphorus and no more than 0.04 percent sulphur. That leaves most of it, 94.25 percent, iron.

The "big" difference between 4140 and 4150? The 4150 has 0.5 percent carbon in it. That extra 0.1 percent makes the 4150 alloy so much harder that it becomes a lot more difficult to work with, but the U.S. Army wants the extra wearability that 4150 offers and is willing to pay for it.

Most rifle makers realize that their customers won't pay the extra costs and find that 4140 is more than good enough. After all, if a .30-06 hunting rifle already has a barrel that will shoot accurately for 5,000 rounds—which is like three lifetimes of hunting—who will pay twice the barrel cost for one that lasts 7,500 rounds?

However, the SAE standards are merely a list of ingredients. When, and at what temperatures you add the alloying constituents also can change the final properties. AR-15 bolts, for instance, are made of a steel known as Carpenter 158. It is a product of the Carpenter steel company, the sole maker, and you won't find it on the SAE list (although if you did it would probably be known as 3310). It's Carpenter's secret, proprietary steel, and if you want it, you buy it from Carpenter.

Are there steels that would work as well, or even better, than Carpenter 158 for AR bolts? Probably. The alloy is a product of 1960s technology, and we've learned a lot since then, but it is enshrined as the mil-spec.

And what about stainless steel? Developed before World War I, stainless steel used in firearms isn't really stainless. It is very rust-resistant, however, not because there is so much chromium but because the chromium on the surface reacts to air to form a passive layer of chromium oxide, which seals the iron from oxidation.

Stainless alloys have their own designations, and the most common of these are the 400 series, and 416 is very popular with manufacturers because it is almost as easy to machine as carbon steel.

Aluminum is used in firearms in two alloys: 7075 and 6061. 6061 is commonly referred to as "aircraft" aluminum and has trace amounts of silicon, copper, manganese, molybdenum and zinc. 7075 is a much stronger alloy and has markedly larger amounts of copper, manganese, chromium and zinc.

Either are strong enough for the tasks we ask of them, but the big reason for 7075 over 6061 in the production of AR receivers, for instance, is corrosion resistance. Early testing in Southeast Asia showed that human sweat, combined with the high temperatures and humidity of the jungle, would simply eat away at 6061 alloy. 7075 just shrugs it off.

Aluminum is too soft to be used bare. To harden its surface, manufacturers use a process known as anodizing. They dunk the aluminum parts in a tank of an acidic solution and pump electricity through it. The result is an accelerated formation of natural oxides that harden the surface.

The oxides are porous, so it is common to use a sealant. The mil-spec process uses a nickel acetate sealant, and the dark color results from the dye used (the natural color left after anodizing is still "aluminum").

What does this mean for us rifle shooters? Well, now you have a better idea of what gun companies (and gun magazines) are talking about when they spew metal specs at you when describing a gun's construction.

Kimber's Hunter Pro Desolve Blak takes the firm's more affordable mountain rifle to new heights.

Contributing Editor for RifleShooter Magazine, Brad Fitzpatrick gives us a review of this modernized version of an iconic favorite.

Scott Rupp gets a chance to talk to Aaron Oelger about a few new products from Hodgdon and why reloading store shelves are empty.

Beth Shimanski of Savage introduces their all new straight-pull rifle. With an Accu-Fit stock and left hand adjustable bolt, this rifle is a perfect choice for anyone!

RifleShooter Magazine editor Scott Rupp breaks down all the features of the Mossberg Patriot Predator rifle chambered in 6.5 PRC.

Introduced in 1965 with the .444 Marlin cartridge, the Model 444 was the most powerful lever action of its day.

J. Scott Rupp takes a first look at the Springfield M1A Loaded rifle chambered in the popular 6.5 Creedmoor.

Tips, techniques, and equipment are applied to these classroom discussions on how to become more proficient and successful at making long-range shots while hunting with AR-platform rifles.

To show viewers how to succeed at long range, J. Guthrie gears up for a challenging shot while chasing Colorado pronghorn at long range with DPMS' Panther 6.5 Creedmoor.

If looking to acquire an automated powder-charge dispensing unit to speed up precision reloading, don't judge the RCBS ChargeMaster Lite powder scale and dispenser by its name; the Little Green machine packs a heavy-weight punch with speed and accuracy.

The new Sako Finnlight II sports an innovative stock and Cerakote metal paired with the terrific 85 action.

The Remington Model Seven is ready, willing and able to handle just about any task.

Give a Gift | Subscriber Services

See All Special Interest Magazines

Get the top Rifle Shooter stories delivered right to your inbox.

All RifleShooter subscribers now have digital access to their magazine content. This means you have the option to read your magazine on most popular phones and tablets.

To get started, click the link below to visit mymagnow.com and learn how to access your digital magazine.

Corrugated Round Bar Offer only for new subscribers.